Lesson 9.1: Human Chromosomes and Genes

Lesson 9.1: Human Chromosomes and Genes

Lesson Objectives

What is a genetic disease?

What is the human genome?

Discuss the importance of characterizing the human genome.

Define autosome and sex-chromosome.

Discuss the importance of SNPs.

What is a karyotype?

Define sex-linked and X-inactivation.

Introduction

As has been previously discussed, genetics is the branch of biology that focuses on heredity. The basics of heredity are similar for all organisms that reproduce sexually: the offspring receive one set of genetic material from one parent and the other set from the other parent. But are there aspects of genetics that are specific for us? Let’s find out.

A genetic disease is a phenotype due to a mutation in a gene or chromosome. Many of these mutations are present at conception and are therefore in every cell of the body. Mutant alleles may be inherited from one or both parents, resulting in a dominant or recessive hereditary disease. Currently, there are over 4,000 known genetic disorders, with many more phenotypes yet to be identified. Theoretically, every human gene, when disrupted due to a mutation, could result in at least one disease-type phenotype. Genetic diseases are typically diagnosed and treated by a geneticist, a medical doctor specializing in these disorders, many of which are extremely rare and difficult to diagnose. Individuals and families with genetic diseases, or suspected genetic diseases, are often counseled by genetic counselors, individuals trained in human genetics and counseling. To understand human genetic diseases, you first need to understand human chromosomes and genes.

The Human Genome

What makes each one of us unique? You could argue that the environment plays a role, and it does to some extent. But most would agree that your parents have something to do with your uniqueness. In fact, it is our genes that make each one of us unique – or at least genetically unique. We all have the genes that make us human: the genes for skin and bones, eyes and ears, fingers and toes, and so on. However, we all have different skin colors, different bone sizes, different eye colors and different ear shapes. In fact, even though we have the same genes, the products of these genes work a little differently in most of us. And that is what makes us unique.

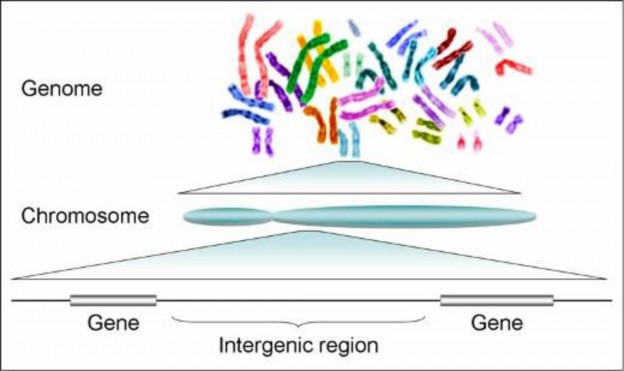

The human genome is the genome - all the DNA - of Homo sapiens. Humans have about 3 billion bases of information, divided into roughly 20,000 genes, which are spread among non-coding sequences and distributed among 24 distinct chromosomes (22 autosomes plus the X and Y sex chromosomes) (Figure 9.1). The genome is all of the hereditary infor- mation encoded in the DNA, including the genes and non-coding sequences. The Human Genome Project (See the Biotechnology chapter) has produced a reference sequence of the human genome. The human genome consists of protein-coding exons, associated introns and regulatory sequences, genes that encode other RNA molecules, and “junk” DNA, regions in which no function as yet been identified.

Chromosomes and Genes

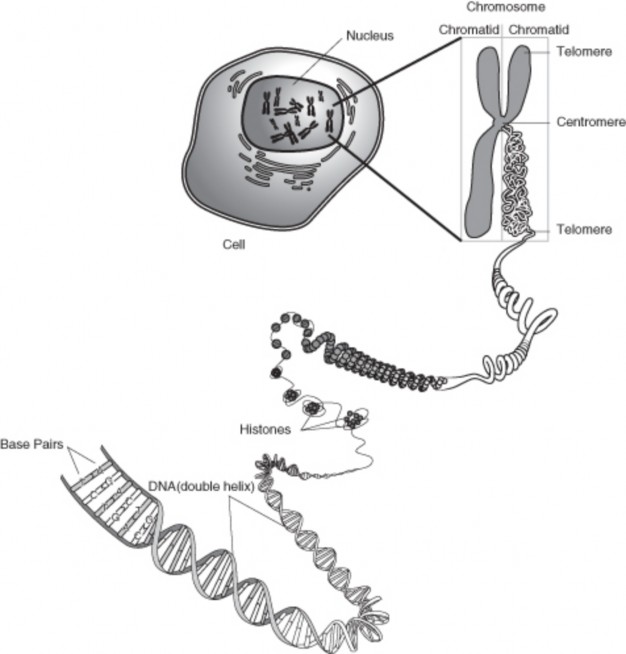

The human genome consists of 24 distinct chromosomes: 22 autosomal chromosomes plus the sex-determining X and Y chromosomes. A chromosome is a threadlike molecule of genes and other DNA located in the nucleus of a cell. Different organisms have different numbers of chromosomes. Human somatic cells have 23 chromosome pairs for a total of 46 chromosomes: two copies of the 22 autosomes (one from each parent), plus an X chromosome from the mother and either an X or Y chromosome from the father (Figure 9.2).

There are an estimated 20,000 human protein-coding genes, but many more proteins. Most human genes have multiple exons separated by much larger introns. Regulatory sequences controlling gene expression are associated with exon sequences. The introns are usually excised (removed) during post-transcriptional modification of the mRNA. Human cells make significant use of alternative splicing (see the Molecular Genetics chapter) to produce a number of different proteins from a single gene. So even though the human genome is surprisingly similar in size to the genomes of simpler organisms, the human proteome is thought to be much larger. A proteome is the complete set of proteins expressed by a

genome, cell, tissue, or organism.

Linkage

As stated above, our roughly 20,000 genes are located on 24 distinct chromosomes. Link- age refers to particular genetic loci, or alleles inherited together, suggesting that they are physically on the same chromosome, and located close together on that chromosome. Two or more loci that are on the same chromosome are physically connected and tend to segregate together during meiosis, unless a cross over event occurs between them. A crossing-over event during prophase I of meiosis is rare between loci that usually segregate together; these loci will usually be close together on the same chromosome. They are, therefore, said to be linked. Alleles for genes on different chromosomes are not linked; they sort independently (independent assortment) of each other during meiosis.

A gene is also said to be linked to a chromosome if it is physically located on that chromosome. For example, a gene (or loci) is said to be linked to the X-chromosome if it is physically located on the X-chromosome chromosome. The physical location of a gene is important when analyzing the inheritance patterns of phenotypes due to that gene. The inheritance patterns of phenotypes may be different if the gene is located on a sex chromosome or an autosome. This will be further discussed in the next lesson.

Linkage Maps

The frequency of recombination refers to the rate of crossing-over (recombination) events between two loci. This frequency can be used to estimate genetic distances between the two loci, and create a linkage map. In other words, the frequency can be used to estimate how close or how far apart the two loci are on the chromosome.

In the early 20th century, Thomas Hunt Morgan, working with the fruit fly Drosophila Melanogaster, demonstrated that the amount of crossing over between linked genes differs. This led to the idea that the frequency of crossover events would indicate the distance separating genes on a chromosome. Morgan’s student, Alfred Sturtevant, developed the first genetic map, also called a linkage map.

Sturtevant proposed that the greater the distance between linked genes, the greater the chance that non-sister chromatids would cross over in the region between the genes during meiosis. By determining the number of recombinants - offspring in which a cross-over event has occured - it is possible to determine the approximate distance between the genes. This distance is called a genetic map unit (m.u.), or a centimorgan, and is defined as the distance between genes for which one product of meiosis in 100 products is a recombinant. So, a recombinant frequency of 1% (1 out of 100) is equivalent to 1 m.u. Loci with a recombinant frequency of 10% would be separated by 10 m.u. The recombination frequency will be 50% when two genes are widely separated on the same chromosome or are located on different chromosomes. This is the natural result of independent assortment. Linked genes have recombination frequencies less than 50%.

Determining recombination frequencies between genes located on the same chromosome al- lows a linkage map to be developed. Linkage mapping is critical for identifying the location of genes that cause genetic diseases.

Variation

As stated above, even though we essentially all have the same genes, the gene products work a little different in all of us, making us unique. That is, the variation within the human genome results in the uniqueness of our species. In fact, genetically speaking, we are all about 99.9% identical. However, it is this 0.1% variation that results in our physical noticeable differences, as well as traumatic events such as illnesses or congenital deformities. These differences can also be used for societies benefits, such as through forensic DNA analysis (discussed in the Biotechnology chapter). Most studies of this genetic variation focus on small differences, know as SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms, which are substitutions in individual bases along a chromosome. For example, the single base change from the sequence GGATAACGTCA to GGAAAACGTCA would be a SNP. Although not occurring uniformly, in the human genome, it has been estimated that SNPs occur every 1 in 100 to 1 in 1000 bases.

DNA sequences that repeat a number of times are known as repetitive sequences or repet- itive elements. For example the sequence CACACACACACACA would be a dinucleotide (2 base) repeat, or the sequence GATCGATCGATCGATCGATC would be a tetranucleotide (4 base) repeat. The genomic loci and length of certain types of repetitive sequences are highly variable from person to person, which is the basis of DNA fingerprinting and DNA paternity testing technologies. Longer repetitive elements are also common in the human genome. Examples of repeat polymorphisms are described in Table 9.1

Table 9.1: Repeat Polymorphisms (bp = base pair)

![]()

Dinucleotide repeats of two bp sequences

![]()

Tetranucleotide repeats of four bp sequences

Microsatellite; Short Tandem Repeats (STRs)

short sequences of 100-200 bp, usually due to repeats of 1-6 bp sequences

Minisatellite short sequences of 6-10 bp repeats

VNTR: Variable Number of Tandem Re- peat

short nucleotide sequence ranging from 14 to 100 nucleotides long, organized into clus- ters of tandem repeats, usually repeated in the range of between 4 and 40 times per loci

Autosomes and Sex Chromosomes

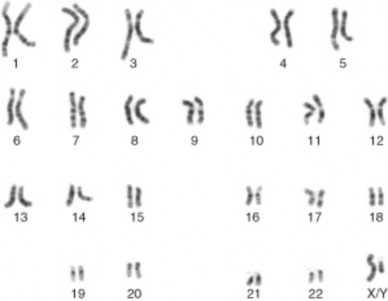

There are 44 autosomes and 2 sex chromosomes in the human genome, for a total of 46 chromosomes (23 pairs). Sex chromosomes specify an organism’s genetic sex. Humans can have two different sex chromosomes, one called X and the other Y. Normal females possess two X chromosomes and normal males one X and one Y. An autosome is any chromosome other than a sex chromosome. Figure 3 9.3 shows a representation of the 24 different human chromosomes. Figure 9.4 shows a karyotype of the human genome. A karyotype depicts, usually in a photograph, the chromosomal complement of an individual, including the number of chromosomes and any large chromosomal abnormalities. Karyotypes use chromosomes from the metaphase stage of mitosis.

The 22 autosomes are numbered based on size, with the largest chromosome labeled chro- mosome 1. These 22 chromosomes occur in homologous pairs in a normal diploid cell, with one of each pair inherited from each parent. The sex of an individual is determined by the sex chromosome within the male gamete. Females are homologous, XX, for the sex chro- mosomes, whereas males are heterozygous, XY. As all individuals inherit an X chromosome from their mother (females can only produce gametes with an X chromosome), it is the sex chromosome that they inherit from their father that determines their sex.

Both autosomal-linked and sex-linked traits and disorders will be discussed later in this chapter.

Sex-Linked Genes

Sex-linked genes are located on either the X or Y chromosome, though it more commonly refers to genes located on the X-chromosome. For that reason, the genetics of sex-linked (or X-linked) diseases, disorders due to mutations in genes on the X-chromosome, results in a phenotype usually only seen in males. This will be discussed in the next lesson.

In humans, the Y chromosome spans 58 million bases and contains about 78 to 86 genes, which code for only 23 distinct proteins, making the Y chromosome one of the smallest chromosomes. The X chromosome, on the other hand, spans more than 153 million bases and represents about 5% of the total DNA in women’s cells, 2.5% in men’s cells. The X chromosome contains about 2,000 genes, however few, if any, have anything to do with sex determination. The Y chromosome is the sex-determining chromosome in humans and most other mammals. In mammals, it contains the gene SRY (sex-determining region Y), which encodes the testes-determining factor and triggers testis development, thus determining sex. It is the presence or absence of the Y chromosome that determines sex.

Figure 9.4: A karyotype of the human genome. Is this from a male or female? (12)

Vocabulary

autosome Any chromosome other than a sex chromosome.

Barr body The inactive X-chromosome in females.

chromosome A threadlike molecule of genes and other DNA wound around histone pro- teins; located in the nucleus of a cell.

genetic counselor An individual trained in human genetics and counseling. genetic disease A phenotype due to a mutation in a gene or chromosome. geneticist A medical doctor specializing in genetic disorders.

genetics The branch of biology that focuses on heredity.

genome All of the hereditary information encoded in the DNA, including the genes and non-coding sequences.

karyotype Depicts, usually in a photograph, the chromosomal complement of an individ- ual, including the number of chromosomes and any large chromosomal abnormalities.

linkage Refers to particular genetic loci or alleles inherited together, suggesting that they are physically on the same chromosome, and located close together on that chromo- some.

microsatellite Short sequences of 100-200 bp, usually due to repeats of 1-6 bp sequences; also known as a STR (Short Tandem Repeat) polymorphism.

minisatellite Short sequence polymorphisms of 6-10 bp repeats.

proteome The complete set of proteins expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism.

repetitive sequences DNA sequences that repeat a number of times; also known as repet- itive elements.

sex chromosomes Specify an organism’s genetic sex; in humans, the X and Y chromo- somes.

sex-linked disease A disorder due to a mutation in a gene on the X-chromosome; also called X-linked disorder.

SNPs Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms; substitutions in individual bases along a gene or chromosome.

SRY Sex-determining region Y; gene which encodes the testes-determining factor and trig- gers testis development, thus determining sex; located on the Y chromosome.

VNTR Variable Number of Tandem Repeat; short nucleotide sequence ranging from 14 to 100 nucleotides long, organized into clusters of tandem repeats, usually repeated in the range between 4 and 40 times per loci.

nactivation

Early in embryonic development in females, one of the two X chromosomes is randomly inactivated in nearly all somatic cells. This process, called X-inactivation, ensures that females, like males, have only one functional copy of the X chromosome in each cell. X- inactivation creates a Barr body, named after their discover, Murray Barr. The Barr body chromosome is generally considered to be inactive, however there are a small number of genes that remain active and are expressed.

Lesson Summary

A genetic disease is a phenotype due to a mutation in a gene or chromosome.

Many of these mutations are present at conception, and are therefore in every cell of the body.

Mutant alleles may be inherited from one of both parents, resulting in a dominant or recessive hereditary disease.

Currently there are over 4,000 known genetic disorders, with many more phenotypes yet identified.

The genome refers to all the DNA of a particular species.

The human genome consists of 24 distinct chromosomes: 22 autosomal chromosomes, plus the sex-determining X and Y chromosomes.

Linkage refers to particular genetic loci or alleles inherited together, suggesting that they are physically on the same chromosome, and located close together on that chromosome.

The variation within the human genome results in the uniqueness of our species.

There are 44 autosomes and 2 sex chromosomes in the human genome, for a total of 46 chromosomes.

Sex chromosomes specify an organism’s genetic sex. Humans have two different sex chromosomes, one called X and the other Y.

Sex-linked genes are located on either the X or Y chromosome, though it more com- monly refers to genes located on the X-chromosome.

Early in embryonic development in females, one of the two X chromosomes is randomly inactivated in nearly all somatic cells. This process is called X-inactivation.

Review Questions

Further Reading / Supplemental Links

What is a genetic disease?

Discuss the main difference between autosomal and sex-linked.

Why is variation within the human genome important?

Why is it more common for males to have X-linked disorders?

Describe how a mutation can lead to a genetic disease.

Discuss how a new mutation can become a new dominant allele.

How are autosomal traits usually inherited? Give examples of traits.

How are genetic diseases usually inherited? Are there exceptions? Research examples.

The National Human Genome research Institute:

The Dolan DNA Learning Center:

http://www.dnalc.org/home_alternate.html

DNA Interactive:

A Science Odyssey: DNA Workshop:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/tryit/dna/

Kimball’s Biology Pages:

http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages

inactivation The random inactivation of one X-chromosome in females; occurs early in embryonic development.

Points to Consider

How are traits inherited? How about the inheritance of genetic disorders? Are inheri- tance patterns of traits and disorders similar?

Could simple Mendelian inheritance account for such complex traits with vast pheno- typic variation such as height or skin color? What do you think?

- Log in or register to post comments

- Email this page