Lesson 12.1: Darwin and The Theory of Evolution

Lesson 12.1: Darwin and The Theory of Evolution

Identify important ideas Darwin developed during the voyage of the Beagle, and give examples of his observations that supported those ideas.

Recognize that scientific theories and discoveries are seldom the work of just one indi- vidual.

Describe prevailing beliefs before Darwin about the origin of species and the age of the earth.

Evaluate Lamarck’s hypothesis about how species changed.

Analyze the impact of Lyell’s Principles of Geology on Darwin’s work.

Evaluate the influence of Malthus’ ideas about human population on Darwin’s thinking.

Discuss the relationship between Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin.

Describe the general ideas of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution.

Use Darwin’s reasoning to explain natural selection as the mechanism of evolution.

Explain how natural selection results in adaptation to environment.

Recognize the importance of variation to species survival.

Relate the idea of differential survival to the concept of natural selection.

Interpret the expression “descent with modification.”

Discuss the concept of “common ancestry.”

Show how Darwin’s theory provides a scientific explanation for the fossil record.

Interpret Darwin’s theory as an example of the general principle that the present arises from the materials and forms of the past.

Introduction

Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution represents a giant leap in human understanding. It explains and unifies all of biology – thousands of years of natural history from before Darwin’s time, as well as the 150 years of genetics, molecular biology, and even ecology since Darwin published the theory. It directs our responses to disease and our practice of agriculture. It enlightens conservation biology. It has the potential to guide our future decisions about biotechnology. Apart from science, the Theory of Evolution has dramatically changed how we think about ourselves and how we relate to the world. Because the theory has influenced so many aspects of human life, it is crucial that you understand it thoroughly.

The “Theory of Evolution” contains two major ideas:

The first is evolution itself.

1. Present life has arisen gradually from past life forms. The millions of species of plants, animals, and microorganisms that live on Earth today are related by descent from common ancestors.

The second describes how evolution happens.

1. Natural selection explains how the diversity of life has arisen through time.

The main goal of this lesson will be to clarify these ideas. The lesson will begin by exploring Darwin’s experiences. The ideas of others who influenced Darwin’s thinking will also be presented. Finally, the content and significance of the theory itself will be analyzed.

The Voyage of the Beagle

Captained by a 26-year-old Royal Navyman and carrying a 22-year-old “gentleman’s com- panion” who collected beetles competitively, His Majesty’s Ship Beagle set sail on one of the shortest days of the year 1831 to chart South American coastal waters. Alarmed by the suicides of his own uncle and the previous Beagle commander, Captain Robert FitzRoy had sought a social and educational equal to accompany him at dinner and in scientific endeav- ors throughout the anticipated two-year voyage. Charles Darwin, financed by his wealthy father, assumed the unpaid positions of the ship’s naturalist and captain’s friend.

Darwin resisted his family’s hopes that he become a doctor or clergyman. During the two years before he dropped out of medical studies, he was repulsed by the brutality of surgery but fascinated by natural history – field observations of plants, animals, rocks, and fossils. He observed marine mammals on the English coast, and learned taxidermy from a freed slave whose talk of rain forests ignited curiosity in Darwin. After his disappointed father switched him to a school of theology, Darwin again gravitated toward natural history,

Figure 12.1: The HMS Beagle carried 22-year-old Charles Darwin as an unpaid naturalist and “gentleman companion” for the ship’s captain. (17)

becoming a protégée of botanist John Steven Henslow in order to learn the popular pastime of competitive beetle collecting. He managed to pass his theology exams, but his interests continued to reflect his passion for natural history, including William Paley’s “argument for divine design in nature.” He had just postponed entry into the clergy in order to study geology – mapping rock layers in Wales – when he received the invitation to join FitzRoy on the Beagle.

Planned to last two years, the voyage shown in Figures 12.1 and 12.2, stretched to five years. Darwin spent over 3 years of this time on land, carefully observing rock formations and collecting animals, plants, and fossils (Figure 12.4). Throughout the journey, he used his observations to develop a series of ideas which later became the foundation for his the- ory of evolution by natural selection (Figure 12.5). A few of his ideas, observations, and experiences follow.

Rock and Fossil Formations

During the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin made a number of geological observations that helped form his theory. Rock and fossil formations that he observed suggested that continents and oceans had changed dramatically over time.

Darwin found rocks at a continental divide, 13,000 feet above sea level, which contained fossil seashells.

A river in Argentina rose gradually through a series of plateaus, which Darwin and FitzRoy interpreted as ancient beaches.

After experiencing a volcanic eruption and an earthquake in Chile, Darwin found a

Figure 12.2: The Beagles voyage continued for nearly five years, although original plans called for only two. Darwin spent over three years of that time on land, collecting plants, animals, and fossils, and developing his ideas about evolution and natural selection. (27)

bed of newly dead mussels, which the quake had lifted nine feet above the sea.

A petrified forest embedded in sandstone at 7,000 feet had been a sunken coastal woodland, buried in sand and then uplifted into mountains.

Near Lima, Darwin recognized coral atolls as the result of sinking volcanoes, with coral adding layer after layer to keep the living reef close to the sunlit surface, as shown inFigure 12.3.

Tropical Rain Forests and Many New Plant, Animal, and Fossil Species

During the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin made a number of observations of plants, animals, and fossils that helped him form his theory. Observations of tropical rain forests and many new plant, animal, and fossil species encouraged Darwin to reconsider the source of the vast diversity of life.

In Brazil, Darwin collected great numbers of insects – especially beetles!

Inland from Montevideo, Darwin dug up the hippopotamus-like skull of an extinct giant capybara.

After collecting his first marsupial in Australia, Darwin exclaimed that some people might think “’Surely two distinct Creators must have been [at] work.”

Figure 12.4: Marine Iguanas (left) and Blue-footed Boobies (right) were among the tremen- dous variety of new and very different plants and animals Darwin identified during the voyage of the Beagle. He developed his ideas about evolution and natural selection to explain the remarkable similarities and differences he had observed. (6)

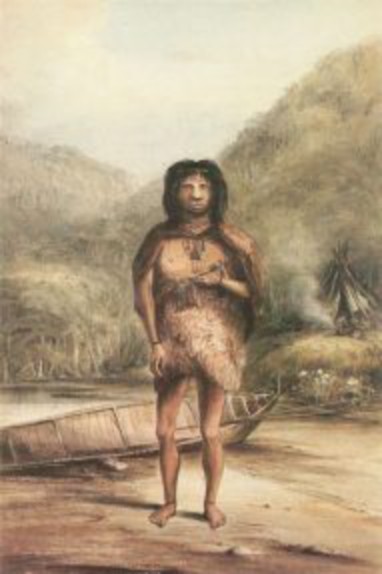

Native Cultures Raised Questions

During the voyage of the Beagle, observations of native cultures led Darwin to question the relationship between humans and animals and the development of civilizations.

Disgusted by the enslavement of blacks in Brazil, Darwin argued with FitzRoy so fiercely that the captain temporarily banished him from dining.

At the tip of South America, Darwin wrote “I could not have believed how wide was the difference between savage and civilized man: it is greater than between a wild and domesticated animal.”

Darwin described New Zealand Maoris as savage, in contrast to missionary-influenced Tahitians.

Jemmy Buttons, a South American native who had “been civilized” in England, chose to stay in South America rather than continue with the Beagle - to the great dismay of the Englishmen convinced of their civilization’s superiority.

Figure 12.5: Darwin’s encounters with native cultures influenced his thinking as much as his discoveries of fossils and new species. This painting was taken from original pictorial records of the Beagle voyage. (23)

Sedimentary Rocks Implied Gradual Changes

Darwin also made a number of observations that implied gradual changes in both the Earth and in living organisms, as opposed to catastrophic changes, including:

Many inland sediments had clearly been deposited by quiet tides rather than catas- trophic floods.

Gauchos, cowboys of Argentina, helped Darwin find and excavate fossils of gigantic extinct mammals, including armadillos and one of the largest mammals of all time, the ground sloth Megatherium (Figure 12.6). Darwin recorded that these sediments bore no trace of a Biblical flood.

Figure 12.6: Darwin found two separate fossils of one of the largest mammals of all time, a giant ground sloth, Megatherium. He noted that they were found in sediments which had been deposited slowly over long periods of time, rather than suddenly as by a catastrophic flood. (31)

Life on Island Chains

The distribution of life on island chains challenged the dogma of the unchangability of species. The Galapagos Islands are arguably where Darwin made his most influential observations. The Galapagos Islands are a group of 16 volcanic islands near the equator about 600 miles from the west coast of South America. Darwin was able to spend months on foot exploring the islands.

Darwin noted that locals could distinguish each island’s variation of Galapagos tortoise, shown in Figure 12.7. Surprisingly, he did not collect their shells, despite dining on the giant reptiles during the voyage.

A series of birds now known as the Galapagos (or Darwin’s) finches were also specific to certain islands. Darwin failed to label the locations in which he had collected these rather drab-looking birds, but fortunately, FitzRoy and the ship’s surgeon were more careful with their collections.

Darwin interpreted the different Galapagos mockingbirds as varieties, but wrote that if varieties were a step on the way to new species, “such facts (would) undermine the stability of Species.”

Figure 12.7: Like many seamen, Darwin and the crew of the Beagle dined on Galapagos tortoise, a convenient animal to carry live on long voyages. However, locals living on the islands claimed the tortoises varied according to the islands from which they came, and this idea later played an important role in Darwin’s thinking about the origins of species. (20)

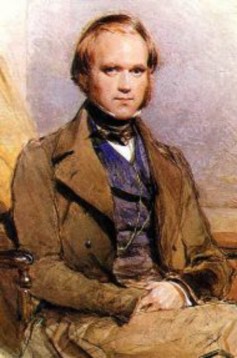

Throughout the trip, Darwin shown in Figure 12.8, sent his mentor, Henslow, collections of plants, animals, insects, and fossils – many of which were previously unknown. While Darwin traveled, Henslow promoted his work by sharing his geological writings and fossils with renowned naturalists. By the time the Beagle returned to England in October of 1836, Darwin himself had been accepted as an established naturalist. His father set up investment accounts to fund his son’s career as a “gentleman scientist.” At that time, governments and universities did not fund scientific research, so only independently wealthy individuals could afford to practice pure science. This position gave Darwin the contacts, resources, and freedom he needed to develop his ideas into the theory of evolution by natural selection.

Figure 12.8: Darwin’s writings on geology and the collections of plants, animals, and fossils he sent back to England established his reputation as a naturalist even before he returned from his voyage. After his return, his father supported him as a “gentleman scientist,” allowing him to further develop the ideas inspired by his Beagle travels. (3)

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Science, like evolution, builds on the past. Darwin’s theory was a product not only of his own intellect, but also of the times in which he lived and the ideas of earlier great thinkers. Some of these ideas colored Darwin’s perspective during his five years on the Beagle; many contributed to his thinking after the voyage. Not until 23 years after he returned to England did Darwin crystallize his thoughts and evidence sufficiently to publish his theory.

Before Darwin, most people believed that all species were created at the same time and remained unchanged throughout history. History, they thought, reached back just 6,000 years.

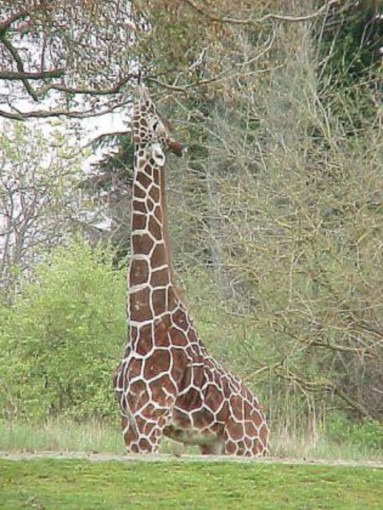

One of the first scientists to explore change in species was Jean Baptiste Lamarck. Lamarck believed that organisms improve traits through increased use, and then pass the improved feature on to their offspring. According to this idea of inheritance of acquired charac- teristics, giraffes have long necks because early giraffes stretched their necks to reach tall trees and then passed the longer necks on to their calves, as shown in Figure 12.9. This attempt to explain adaptation was popular during the 19thcentury, and undoubtedly in- fluenced Darwin’s thinking. Although Lamarck advanced the proposal that species change, evidence does not support inheritance of acquired characteristics. You can weight-train for years, but unless your children train as hard as you did, their muscles will never match yours! We will look later at Darwin’s explanation for giraffes’ necks.

Much as Lamarck questioned the dogma that species do not change, Charles Lyell challenged the belief that the earth was young. In Principles of Geology, he recorded detailed observa- tions of rocks and fossils, and used present patterns and processes as keys to past events. He concluded that many small changes over long periods of time built today’s landscapes, and that the earth must be far older than most people believed. Captain FitzRoy gave Darwin a copy of Principles of Geology just before the Beagle left England, and Darwin “saw through [Lyell’s] eyes” during the voyage. Darwin’s theory that present species developed gradually over long periods of time reflects Lyell’s influence.

The idea that natural laws, rather than miracles, govern life as well as geology grew during the early 19th century. Charles Babbage wrote that God had the power to make laws, which in time produce species. His close friend, John Herschel, called for a search for natural laws underlying the ”mystery of mysteries” of how species formed. Later, Darwin cited Herschel as “one of our greatest philosophers” and then said he intended ”to throw some light on the origin of species — that mystery of mysteries.”

Darwin’s idea that individuals in a population compete for resources came from reading Thomas Malthus. Malthus described a human “struggle for existence” due to exponential population growth and limited food. Darwin thought that animal and plant populations might have similarly limited resources. If so, offspring suited to their environment would be more likely to survive, while those less “fit” would perish.

Breeders of pigeons, dogs, and cattle inspired Darwin’s ideas about selection. By choosing

which animals reproduced, breeders could achieve remarkable changes and diversity in a relatively short time. Variations in traits were clearly abundant and heritable. Darwin referred to selective breeding as artificial selection. His observations of how artificial selection worked helped him to develop his concept of natural selection (Figure 12.10).

Figure 12.10: The way in which animal breeding artificially selects desirable variations in- fluenced Darwin’s ideas of natural selection. The English Carrier Pigeon (left), the English Fantail (center), and the Fiary Swallow (right) have all “descended” from the common rock pigeon (Columbia livia), with the help of human breeders. (24)

One of the last individuals to influence Darwin’s theory was Alfred Russel Wallace, a nat- uralist whose work in Malaysia led him to conclusions similar to Darwin’s. In 1858 - over 20 years since the Beagle returned to England - Wallace sent Darwin a paper which de- scribed concepts nearly identical to Darwin’s ideas about evolution and natural selection. Lyell helped arrange a joint presentation to the Linnean society two weeks later. Darwin, shocked by the sudden competition, worked quickly to complete his book by the following year. Although both naturalists had independently come to the same conclusions, the ex- tensive evidence and careful logic Darwin presented in The Origin of the Species earned him the greater share of recognition for the theory of evolution by natural selection.

Standing on the shoulders of the giants who went before him, Darwin was able to see past the countless details of his beloved work in natural history to formulate a unifying theory to explain the diversity of life.

Darwin’s Theory of Evolution

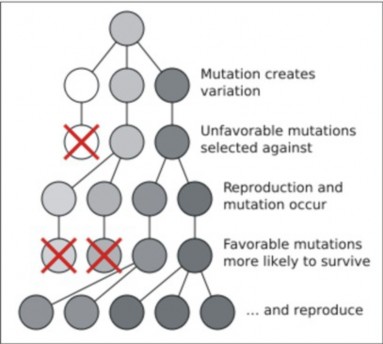

Darwin lived in an increasingly scientific society which had begun to accept the idea that universal ”laws” governed processes in nature - perhaps including life itself. Like Lamarck, Darwin understood that species change. With Lyell, he saw that the history of Earth and its life covered a vast amount of time. From his observations of animal breeding, he recognized that even within species, individuals showed variation in traits, and that the variations could be passed to offspring. Recalling Malthus, he knew that populations could produce far more offspring than the environment could support. He predicted that individuals with traits which suited the environment would survive and reproduce to pass their favorable traits to offspring, as shown in Figure 12.11. Those whose traits were less suited to the environment would die. Just as humans select for breeding those cattle which produce more milk, he reasoned, nature (the limited environment) selects individuals which use resources most efficiently. Thus, he called his explanation of how species change natural selection.

Darwin defined natural selection as the ”principle by which each slight variation [of a trait], if useful, is preserved,” and he later regretted that he had not named it “natural preservation.” Today it is often defined as the process by which a certain trait becomes more common within a population. Let’s look once more at the parts of this process, and then we will consider its consequences.

By chance, heritable variations exist within a species.

Darwin did not know that genes made of DNA determine traits. Much later, scientists learned that mutations in DNA can change genes and produce variations in traits. However, his observations of animal breeding and his detailed studies of barnacles and orchids con- vinced him that small, heritable variations in traits were common among individuals within a species. Darwin probably recognized that sexual reproduction increased variety in off- spring. He expressed considerable concern that his own health problems might be heritable, especially when his beloved daughter Annie grew ill and died. He believed that his marriage to his cousin may have contributed to his children’s weaknesses.

Species produce more offspring than can survive.

Malthus argued that human populations grow exponentially if unchecked, but that disease, starvation, or war will limit population growth eventually. High birth rates and high death rates were characteristic of human history. Darwin himself had ten children; three died before maturity. Darwin reasoned that all species had the capacity to grow. However, his observations showed that most populations remained stable due to environmental limits. He concluded that many offspring must die. The phrases overproduction of offspring and struggle for existence summarize this idea.

Offspring with favorable variations are more likely to survive to reproduce.

Although heritable variations appeared to be random, death, Darwin reasoned, was not. Offspring which, by chance, had variations which “fit” or adapted them to their environment would have a greater chance to survive to maturity and a greater chance to reproduce. Offspring without such adaptations were more likely to die. Thus, well-adapted individuals produce more offspring. Differential survival and reproduction is a cornerstone of natural selection.

Gradually, individuals with favorable variations make up more of the population.

Can an individual organism evolve? No. Though an individual organism can be better adapted to its environment, it still must mate with others of its species, so by definition, it is not a new species. It is just an individual with a better chance of survival in its environment. It is the accumulation of many adaptations that, over many generations, results in a new species.

Through chance variation, overproduction of offspring, and differential survival and repro- duction, the proportion of individuals with a favorable trait (or favorable phenotype) will increase. The result is a population of individuals adapted to their environment. It is the variation within a species that increases the likelihood that at least some members of a species will be adapted to their environment and survive under changed conditions.

It is important to note that natural selection is not directed or intentional. It depends on chance variations - due to genetic variations - and can work only with the “raw material” of existing species. Occasionally, variations which have no particular adaptive logic may survive. However, the limits set by resources and environment usually mean an increase in traits which help survival or reproduction, and the loss of traits which harm them. Gradually, species change. Eventually, changes accumulate and a new species is formed.

Let’s compare natural selection to inheritance of acquired characteristics (Lamarck’s idea mentioned above). How would Darwin’s mechanism explain the long necks of giraffes?

Recall that Lamarck believed that giraffes could stretch their necks to reach tall trees, and pass their stretched necks on to offspring. If this were true, evolution would reward effort toward a goal. Darwin showed that evolution is not goal-directed. Instead, the environment reinforces variations which occur by chance.

Lyell studied the geology which surrounded him and saw that the environment had changed many times over a vast amount of time. Darwin studied the life across continents and saw, in addition to tremendous variation, that species had changed – in response to the changes in their environment – over that vast amount of time. Both proved, with careful observations and well-reasoned inferences, that the present arises from the past. Limited to our brief lifespans, we see today’s species as fixed. Darwin taught us how to see the relationships between them; to see that they developed from earlier, distinctly different species; to see that all of them - all of us - share common ancestors (Figure 12.12). The cartoons which showed Darwin as an ape (an example is shown in the next lesson) did a great disservice to his theory of evolution. Far too many people limit their understanding of evolution to the simple phrase that “we came from apes.” We humans share common ancestors not only with the great apes, but with ALL of life – blue whales, gazelles, redwood trees, saguaros, fireflies, mosquitoes, puffballs, amebas, and bacteria. As Darwin said in closing the Origin, “There is grandeur in this view of life.”

Darwin delighted in the great diversity of life, but also saw unity within that diversity. He saw striking patterns in the similarities and differences. Seeking an explanation for those patterns, he developed the concept of natural selection. Natural selection explains how today’s organisms could be related – through “descent with modification” from common ancestors. Natural selection explains the story told by the fossil record – the long history of life on Earth. Natural selection is a scientific answer (if only partial) to the old questions: Who are we? How did we come to be?

Figure 12.12: A sketch from Darwin’s Origin of Species, this ”Tree of Life” depicts his ideas of how today’s species (top row, XIV) have descended with modification from common ancestors. The theory implies that all species living today have a universal common ancestor

Heritable variation: In the past, some giraffes had short necks, and some had long necks.

Overproduction of offspring: Giraffes produced more young than the trees in their environment could support.

Differential survival and reproduction: Because the long-necked giraffes could feed from taller trees, they were more likely to survive and produce more offspring. Short-necked giraffes were more likely to starve before they could reproduce.

Species change: The long-necked giraffes passed their long necks on to their calves, so that each generation, the population contained more long-necked giraffes.

that we humans are related to all of Earth’s plants, animals, and microorganisms. (34)

In the light of natural selection, it is easy to see that variation – differences among individuals within a population – increases the chance that at least some individuals will survive if the environment changes. Here is a strong argument against cloning humans: if we were all genetically identical – if variation (or genetic variation) did not exist – a virus which previously could kill just some of us would either kill all of us, or none of us. Throughout the long history of life, variation has provided insurance that inevitable changes in the environmental will not mean the extinction of a species. Similarly, the diversity of species ensures that environmental change will not mean the extinction of life. Life has evolved (or, the Earth’s changing environment has selected) variation and diversity because they ensure survival. Causes of mutation may have pre-existed, but in a sense, life has embraced them. And sexual reproduction has evolved to add further to variation and diversity (as discussed in the Cell Division and Reproduction chapter).

Adaptations are logical because the environment imposes limits on organisms, selecting against those who do not “fit.” Adaptations arise through gradual accumulation of chance variations, so they cannot be predicted, despite the fact that they appear to be goal-directed or intentional. Adaptations relate to every aspect of life: food, water, oxygen, nutrients, shelter, growth, response, reproduction, movement, behavior, ability to learn. Adaptations connect organisms to the resources in their environments. You are born with your adapta- tions; they are not changes you make to fit yourself into an environment. If the environment changes, the adaptive value of some of your inherited characteristics may also change. Our human appetites for salt and fat, for example, may remain from our past, when fat and salt were rare in our environment; now that they are easily available, we consume more than is good for us. Biologist E.O. Wilson believes adaptations reach every aspect of human life - that social, political, and even religious behaviors are rooted in our genes. Of course, we can learn – and learning allows us to adapt within our lifetimes to environmental change. The ability to learn is itself an adaptation – perhaps our greatest gift. But more and more, we are discovering that much of our behavior – including learning - is genetically programmed

a gift from our ancestors similar to vision and hearing, or breathing and digestion.

Darwin’s theory can be summarized in two statements All living species share com- mon ancestors, and

Natural selection explains how species change.

In this lesson, we have explored Darwin’s reasoning. In the next lesson, we will consider the abundant evidence which supports his ideas.

Lesson Summary

The Theory of Evolution has changed how we see ourselves and how we relate to our world.

The theory has two basic ideas: the common ancestry of all life, and natural selection.

Darwin studied medicine and theology, but he first worked as ship’s naturalist on the HMS Beagle.

During the 5-year voyage, Darwin spent over 3 years on land exploring new rocks, fossils, and species.

From his observations, Darwin developed new ideas which later formed the foundation of his theory.

Rock and fossil formations suggested that continents and oceans had changed dramat- ically.

Tropical rain forests encouraged Darwin to reconsider the source of the vast diversity of life.

Native cultures raised questions about the relationship between humans and animals.

Sedimentary rocks implied gradual, as opposed to catastrophic, changes in the earth and in life.

The distribution of life on island chains challenged the dogma of the immutability of species.

After he returned, his reputation as a naturalist and his father’s financial support allowed him to become a “gentleman scientist,” free to analyze his collections, formulate his theory, and write about both.

Like all scientific theories, Darwin’s was a product of both his own work and the work of other scientists.

Before Darwin, most people believed that all species were created and unchanging about 6000 years ago.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed that acquired characteristics could be inherited. Evi- dence did not support his mechanism for change, but Darwin shared his ideas of change in species.

Charles Lyell wrote that present rock formations have developed through gradual changes over long periods of time. Darwin applied his ideas to present life forms.

Observations of animal breeding helped Darwin appreciate the importance of heritable variations.

Malthus’ work showed that populations produce more offspring than the environment can support.

Charles Babbage and John Herschel believed that natural laws governed the origin of species.

Alfred Russel Wallace formulated a theory very similar to Darwin’s. Although they collaborated on a joint paper, Darwin’s clear and forceful Origin of Species earned him greater credit.

The two general ideas of Darwin’s Theory are evolution and natural selection.

The concept of natural selection includes these observations and conclusions:

By chance, heritable variations exist within a species.

Species produce more offspring than can survive.

Offspring with favorable variations are more likely to survive to reproduce.

Gradually, individuals with favorable variations make up more of the population.

Variation among individuals within species ensures that some will survive environmen- tal change.

Because some variations help survival in a specific habitat more than others, individuals having those variations are more likely to survive and reproduce.

This differential survival and reproduction results in a population which is adapted to its environment.

The result of natural selection is gradual change in species, and when enough changes have accumulated, new species form. This is “descent with modification.”

The idea that natural selection has led to the origin of all species, together with evidence from the fossil record, means that all existing species are related by “common ancestry.”

Evolution by natural selection explains the history of life as recorded in the fossil record.

Common ancestry explains the similarities, and natural selection in the face of envi- ronmental change explains the differences among present-day species.

Like Lyell’s Principles of Geology, Darwin’s Theory of Evolution supports the general principle that the present arises from the materials and forms of the past.

Review Questions

State 3 of the 5 ideas Darwin developed during the Voyage of the Beagle. For each idea, give and example of a specific observation he made which supports the idea.

Compare and contrast Darwin’s position as a “gentleman scientist” with today’s pro- fessional scientists.

What does the expression “standing on the shoulders of giants” say about Darwin and his Theory of Evolution? Support your interpretation with at least three specific examples.

Explain the importance of Lyell’s Principles of Geology to Darwin’s work.

Discuss the influence of animal breeding on Darwin’s thinking.

Clarify the relationship between Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace.

Summarize in your own words the two basic ideas which make up Darwin’s Theory of Evolution.

Compare and contrast Lamarck’s and Darwin’s ideas using the evolution of the human brain as an example.

Why is it incorrect to say that evolution means organisms adapt to environmental change?

Why is it not correct to say that evolution means “we came from monkeys?”

Further Reading / Supplemental Links

http://www.aboutdarwin.com/voyage/voyage03.html

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/evolution.html

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/

http://www.literature.org/authors/darwin-charles/the-origin-of-species/

http://www.life.umd.edu/emeritus/reveal/pbio/darwin/darwindex.html

Vocabulary

adaptation A characteristic which helps an organism survive in a specific habitat.

artificial selection Animal or plant breeding; artificially choosing which individuals will reproduce according to desirable traits.

inheritance of acquired characteristics The idea that organisms can increase the size or improve the function of a characteristic through use, and then pass the improved trait on to offspring.

law A statement which reliably describes a certain set of observations in nature; usually testable.

natural selection The process by which a certain trait becomes more common within a population, including heritable variation, overproduction of offspring, and differential survival and reproduction.

theory An explanation which ties together or unifies a large group of observations.

Points to Consider

How might the Theory of Evolution help us to understand and fight disease?

What other aspects of medicine could benefit from an understanding of evolution?

How can evolution and natural selection improve conservation of species and their environments?

How would you put into words the ways in which evolution has changed the way we look at ourselves?

How do you think it has altered the way we relate to other species? To the Earth?

Consider the human brain. If Lamarck’s hypothesis about inheritance of acquired characteristics were true, how would your knowledge compare to your parents?

- Log in or register to post comments

- Email this page